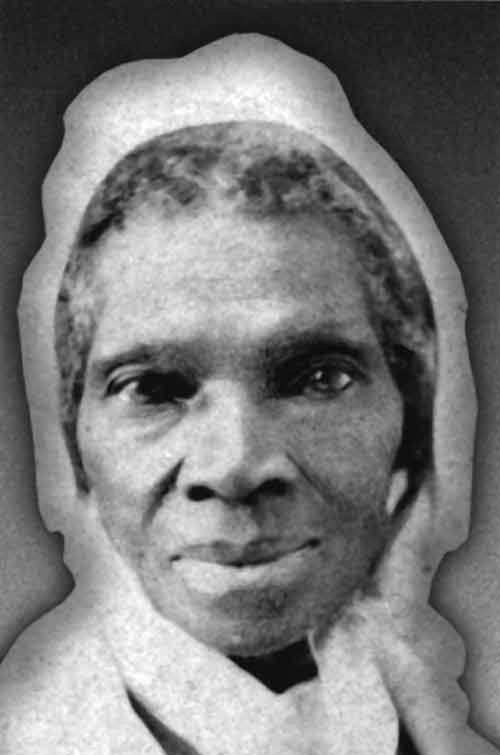

A Woman Named Truth

A Woman Named Truth

[Originally published January 28, 2026]

In the year 1797, a tiny baby girl was born in a small cabin about ninety-five miles north of New York City in the town of Esopus, a small hilly settlement called Swartekill. Isabella was the daughter of James and Elizabeth Bomefree, who were brought from Ghana and Guinea by slave traders and sold to Col. Johannes Hardenbergh. Her first prayers were in Dutch, asking God about her dozen siblings, all of whom had been sold into enslavement. She never received a formal education, but learned the scriptures from the oral recitations and story-telling of the older members of her enslaved community.

Growing up as the property of another human, Bella (as she was called) knew harsh conditions. She was forced into labor at just five years old and at nine, was separated from her parents and sold. By the time of her final sale at thirteen, three owners later, she had suffered unspeakable indignities. When Bella was eighteen, she fell in love with Robert, an enslaved man from a neighboring farm. Their love ended tragically when Robert’s owner had him murdered. Later, with another enslaved man, Bella had a son, Peter, and her daughters, Diana, Elizabeth, and Sophia.

In 1827, a piece of New York legislation set July 4 as the date when all remaining enslaved people in New York would be freed, but Bella's owner said he would refuse to abide by the law. So, after much agony of spirit and prayer, she left her three older children with a trusted friend, took baby Sophia, and escaped in 1826, a full year before the deadline. Soon after, Bella found refuge with Quakers Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen, an abolitionist family in New Paltz, New York, who purchased her freedom for twenty dollars. To mark this new chapter, she changed her last name to Isabella Van Wagenen.

Here Bella was able to breathe, to pray, to learn, and at last found a new relationship with Christ. With the support of the Van Wagenens, she successfully sued for the return of her five-year-old son, Peter. Shortly after her escape, her former enslaver had illegally sold Peter to traders who took him to Alabama, despite emancipation laws requiring him to remain in New York until he turned twenty-eight. Determined to fight this injustice, one that echoed the pain she and her siblings had endured, Bella demanded that local law enforcement intervene. After a year-long legal battle, a judge of the Ulster County Courthouse ruled in her favor, making her the first Black woman to sue a White man and win.

In 1829, Bella and her son moved to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a preacher. Three years later, she left to work for another preacher, Robert Matthews. During these years and the next decade, she participated in the religious revivals sweeping the state, becoming a charismatic speaker and finding God to be real and powerful in her life. She formed connections with Black community leaders and became active in abolition, women’s rights, and pacifism. In 1843 she sensed a call from God to travel the countryside and proclaim His truth, so she took a new name - Sojourner Truth.

She toured the country over the next number of years, often wearing a sash reading, “Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.” She supported herself through the sale of her autobiography, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a work which she wrote and dictated to her friend Olive Gilbert in 1850. With a quick wit and an intensely engaging personality, Sojourner became a popular speaker. She met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and, thereafter, added the cause of women’s rights to her lectures, delivering her famed “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at a convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851.

At the invitation of Quaker friends in 1857, Truth moved to their village of Harmonia, Michigan, on the outskirts of Battle Creek. Although she continued to travel widely, Battle Creek would now be home to Truth, her children, and grandchildren. During the Civil War, she worked tirelessly to ensure that troops of color were treated fairly, even assembling care packages for them. She became friends with William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, speaking publicly about the evils of slavery, solidifying her role as a powerful advocate for social justice. She met with President Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C. and, in 1865, sued and won a judgment against a streetcar company that led to the desegregation of such conveyances. After the war, she also served as a counselor to newly-freed slaves in Virginia, helping to provide them with skills needed to achieve self-sufficiency.

In the late 1860s, Truth advocated for land grants for freed Black Americans. She also met President Ulysses S. Grant and worked on his re-election campaign. In 1872, she attempted to vote in the presidential election, but was turned away, for women could not yet vote. Despite her declining health, Truth continued her advocacy efforts and spent her final years in Michigan. She died at her home on November 26, 1883 at the age of eighty-six, and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, where her tombstone still stands tall today.

Many libraries, statues and busts, monuments, plazas, and schools are named after this woman named "Truth." This month, we honor the truth-tellers who, because of their trust in the God of truth, risk all to work against evil. We are better in our day because Truth lived and spoke with such courage in hers.

-Karen O'Dell Bullock

Growing up as the property of another human, Bella (as she was called) knew harsh conditions. She was forced into labor at just five years old and at nine, was separated from her parents and sold. By the time of her final sale at thirteen, three owners later, she had suffered unspeakable indignities. When Bella was eighteen, she fell in love with Robert, an enslaved man from a neighboring farm. Their love ended tragically when Robert’s owner had him murdered. Later, with another enslaved man, Bella had a son, Peter, and her daughters, Diana, Elizabeth, and Sophia.

In 1827, a piece of New York legislation set July 4 as the date when all remaining enslaved people in New York would be freed, but Bella's owner said he would refuse to abide by the law. So, after much agony of spirit and prayer, she left her three older children with a trusted friend, took baby Sophia, and escaped in 1826, a full year before the deadline. Soon after, Bella found refuge with Quakers Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen, an abolitionist family in New Paltz, New York, who purchased her freedom for twenty dollars. To mark this new chapter, she changed her last name to Isabella Van Wagenen.

Here Bella was able to breathe, to pray, to learn, and at last found a new relationship with Christ. With the support of the Van Wagenens, she successfully sued for the return of her five-year-old son, Peter. Shortly after her escape, her former enslaver had illegally sold Peter to traders who took him to Alabama, despite emancipation laws requiring him to remain in New York until he turned twenty-eight. Determined to fight this injustice, one that echoed the pain she and her siblings had endured, Bella demanded that local law enforcement intervene. After a year-long legal battle, a judge of the Ulster County Courthouse ruled in her favor, making her the first Black woman to sue a White man and win.

In 1829, Bella and her son moved to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a preacher. Three years later, she left to work for another preacher, Robert Matthews. During these years and the next decade, she participated in the religious revivals sweeping the state, becoming a charismatic speaker and finding God to be real and powerful in her life. She formed connections with Black community leaders and became active in abolition, women’s rights, and pacifism. In 1843 she sensed a call from God to travel the countryside and proclaim His truth, so she took a new name - Sojourner Truth.

She toured the country over the next number of years, often wearing a sash reading, “Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.” She supported herself through the sale of her autobiography, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a work which she wrote and dictated to her friend Olive Gilbert in 1850. With a quick wit and an intensely engaging personality, Sojourner became a popular speaker. She met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and, thereafter, added the cause of women’s rights to her lectures, delivering her famed “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at a convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851.

At the invitation of Quaker friends in 1857, Truth moved to their village of Harmonia, Michigan, on the outskirts of Battle Creek. Although she continued to travel widely, Battle Creek would now be home to Truth, her children, and grandchildren. During the Civil War, she worked tirelessly to ensure that troops of color were treated fairly, even assembling care packages for them. She became friends with William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, speaking publicly about the evils of slavery, solidifying her role as a powerful advocate for social justice. She met with President Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C. and, in 1865, sued and won a judgment against a streetcar company that led to the desegregation of such conveyances. After the war, she also served as a counselor to newly-freed slaves in Virginia, helping to provide them with skills needed to achieve self-sufficiency.

In the late 1860s, Truth advocated for land grants for freed Black Americans. She also met President Ulysses S. Grant and worked on his re-election campaign. In 1872, she attempted to vote in the presidential election, but was turned away, for women could not yet vote. Despite her declining health, Truth continued her advocacy efforts and spent her final years in Michigan. She died at her home on November 26, 1883 at the age of eighty-six, and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, where her tombstone still stands tall today.

Many libraries, statues and busts, monuments, plazas, and schools are named after this woman named "Truth." This month, we honor the truth-tellers who, because of their trust in the God of truth, risk all to work against evil. We are better in our day because Truth lived and spoke with such courage in hers.

-Karen O'Dell Bullock

Posted in PeaceWeavers