Who Truly is My Neighbor?: Placing the Spotlight on Human Trafficking

Who Truly is My Neighbor?

Placing the Spotlight on Human Trafficking

Introduction

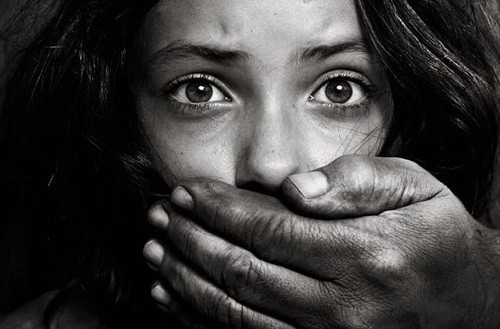

"Who is my neighbor?" will bring to the minds of most Christians the "Parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10. The question is morally load-bearing because Jesus exposes the depth of depravity in the heart of a man who outwardly was recognized as being a law-keeper. Hopefully, my pen will cause you to imagine the change in tone when I ask the question in light of a global moral issue, human trafficking. "Who truly is my neighbor?" will cause us to consider that upstanding community members may well be filled with unimaginable evil in their hearts and actions. Let's consider the heinous crime of human trafficking and ways to combat this global evil.

Millions of lives impacted by force, fraud, or coercion

Human trafficking involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act. This crime differs from, but may be related to, human smuggling, which includes the illegal movement of someone across a border. It involves the "transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons by improper means (such as force, abduction, fraud, or coercion)" for a second crime that includes forced labor or sexual exploitation. The three types of human trafficking are sex trafficking, forced labor, and domestic servitude. A person may be coerced to engage in sex acts for money, required to labor for little or no pay, or work in homes as nannies, maids, or domestic help with no means of escape.

Human trafficking is clouded by uncertainty. Due to the covert nature of this crime, estimates of the actual numbers of persons who are trafficked is uncertain; however, the US government approximated in 2024 that 27 million persons were trafficked for labor, services, and commercial sex. The common denominator, however, between the widely varying estimates is heartbreaking: vulnerability due to gender, ethnicity, poverty, and the hope for a better life. Human trafficking in the United States can happen to anyone and occurs in cities, suburbs, and rural towns, even in Hood County.

Human trafficking wears the face of governments, businesses large and small, crime organizations, and even individuals, often occurring in plain view because governments and law enforcement agencies have often placed higher priority on policing the international drug trade than such egregious crimes against these victims. Ironically, organized crime's new "drug" includes the illegal sale of human lives because people, unlike a dosage, can be sold repeatedly.

Human trafficking is extraordinarily lucrative. Existing global economic disparities between the "haves" and "have-nots," low-cost transportation, as well as a rise in tourism (cf. pedophiles and sex tourism) create a perfect storm for the abuse of vulnerable human lives. The problem is transnational in scope and viewed as an economic "golden egg" with human beings exploited for a variety of reasons--sexual, labor, marriage, begging, service as child soldiers, and for their organ harvestation. Modern slavery and human trafficking are estimated to produce $236 billion dollars annually for criminals! Human trafficking impacts negatively not only those who are abused, but also destroys common global moral principles, such as justice, human rights, and life's sanctity. These circumstances beg the question: How do we recognize a human trafficker?

Human trafficking is clouded by uncertainty. Due to the covert nature of this crime, estimates of the actual numbers of persons who are trafficked is uncertain; however, the US government approximated in 2024 that 27 million persons were trafficked for labor, services, and commercial sex. The common denominator, however, between the widely varying estimates is heartbreaking: vulnerability due to gender, ethnicity, poverty, and the hope for a better life. Human trafficking in the United States can happen to anyone and occurs in cities, suburbs, and rural towns, even in Hood County.

Human trafficking wears the face of governments, businesses large and small, crime organizations, and even individuals, often occurring in plain view because governments and law enforcement agencies have often placed higher priority on policing the international drug trade than such egregious crimes against these victims. Ironically, organized crime's new "drug" includes the illegal sale of human lives because people, unlike a dosage, can be sold repeatedly.

Human trafficking is extraordinarily lucrative. Existing global economic disparities between the "haves" and "have-nots," low-cost transportation, as well as a rise in tourism (cf. pedophiles and sex tourism) create a perfect storm for the abuse of vulnerable human lives. The problem is transnational in scope and viewed as an economic "golden egg" with human beings exploited for a variety of reasons--sexual, labor, marriage, begging, service as child soldiers, and for their organ harvestation. Modern slavery and human trafficking are estimated to produce $236 billion dollars annually for criminals! Human trafficking impacts negatively not only those who are abused, but also destroys common global moral principles, such as justice, human rights, and life's sanctity. These circumstances beg the question: How do we recognize a human trafficker?

Who truly is my Good Samaritan?

Traffickers exhibit signs that are eerily like the behavior of the lawyer in Luke 10:25-37. Keep in mind, I am not suggesting that the barrister that tested Jesus with a question about eternal life was a human trafficker, only that there are some moral clues he displayed that expose his inner moral depravity and lack of neighborliness! We can glean two key biblical moral principles that expose the lack of authentic neighborliness as we strive to secure our communities.

Rationalization. First, the lawyer's moral views were shaped though the lens of his own interpretation of the Old Testament moral code. He was not an honest seeker of how to inherit eternal life. Jesus shows the lawyer that the standard for measuring fulfillment of the law is not judged on an individual basis (10:27; “as yourself”). In other words, I do not get to build my own road to life eternal with whatever moral material I choose. The lawyer rationalized his own behavior to justify himself, which is a characteristic of traffickers. They often believe that the person being exploited would not have any hope of a better life were it not for them. They often are heard to say, "If I don't do it (exploit this person) somebody else will.” It appears that the limiting of God’s demands to lessen one’s responsibility was a popular Jewish pastime and remains quite common, even today (10:29).

Dehumanization. Our road to eternal life is bound up with our neighbors. Notice that Jesus focused not on the object of neighborly love, but on the subject—“the Samaritan who made himself a neighbor” (10:36; EBC). Love is demonstrated in action. In the case of the Samaritan, in his acts of mercy to a vulnerable human life. In direct contrast, however, traffickers notoriously groom, manipulate, control, and exploit the vulnerable for their own ends. Culture often marginalizes people and traffickers use societal rejection as the open door to abuse. They do not see the intrinsic value of those lives they devour. The point? God will not bestow the “life of the kingdom on those who reject the command to love” (EBC). In other words, life in Christ is not first about asking, “Who is my neighbor?” It begins by asking, “Am I truly neighborly?” Traffickers are not neighborly.

Rationalization. First, the lawyer's moral views were shaped though the lens of his own interpretation of the Old Testament moral code. He was not an honest seeker of how to inherit eternal life. Jesus shows the lawyer that the standard for measuring fulfillment of the law is not judged on an individual basis (10:27; “as yourself”). In other words, I do not get to build my own road to life eternal with whatever moral material I choose. The lawyer rationalized his own behavior to justify himself, which is a characteristic of traffickers. They often believe that the person being exploited would not have any hope of a better life were it not for them. They often are heard to say, "If I don't do it (exploit this person) somebody else will.” It appears that the limiting of God’s demands to lessen one’s responsibility was a popular Jewish pastime and remains quite common, even today (10:29).

Dehumanization. Our road to eternal life is bound up with our neighbors. Notice that Jesus focused not on the object of neighborly love, but on the subject—“the Samaritan who made himself a neighbor” (10:36; EBC). Love is demonstrated in action. In the case of the Samaritan, in his acts of mercy to a vulnerable human life. In direct contrast, however, traffickers notoriously groom, manipulate, control, and exploit the vulnerable for their own ends. Culture often marginalizes people and traffickers use societal rejection as the open door to abuse. They do not see the intrinsic value of those lives they devour. The point? God will not bestow the “life of the kingdom on those who reject the command to love” (EBC). In other words, life in Christ is not first about asking, “Who is my neighbor?” It begins by asking, “Am I truly neighborly?” Traffickers are not neighborly.

Rescuing the vulnerable begins with our hearts

Christians should not behave like the priest and Levite in Christ's parable. Human trafficking is enslavement, and stems from the dehumanization of life. Ethically, dehumanization in all its forms is unjust because it denies equal dignity to another life by ignoring a person in need or treating a human life as a commodity to be bartered or sold.

Secondly, a foundational moral principle of human rights is a right to non-interference with one's person. Tragically, while this moral concept is a bedrock standard of democratic forms of government, both democracies (e.g. "turning a blind eye") and many totalitarian regimes (e.g. forced sex slave trade or forced child military service) worldwide actually allow or perpetrate harm upon their own citizens.

Thirdly, both non-religious and religious conceptions of life's sanctity emphasize the equal dignity of persons and the absolute inviolability of human life as being created in God's image (Genesis 1:27). The age-old moral reality is that basic principles are often ignored or compromised at the point of ethical practice. One wonders what Christians may begin to do to put an end to human trafficking.

Secondly, a foundational moral principle of human rights is a right to non-interference with one's person. Tragically, while this moral concept is a bedrock standard of democratic forms of government, both democracies (e.g. "turning a blind eye") and many totalitarian regimes (e.g. forced sex slave trade or forced child military service) worldwide actually allow or perpetrate harm upon their own citizens.

Thirdly, both non-religious and religious conceptions of life's sanctity emphasize the equal dignity of persons and the absolute inviolability of human life as being created in God's image (Genesis 1:27). The age-old moral reality is that basic principles are often ignored or compromised at the point of ethical practice. One wonders what Christians may begin to do to put an end to human trafficking.

A way forward

Apply biblical principles to current moral concerns. The elusive and pervasive nature of human trafficking does stem from some common roots. On a theoretical level, the dehumanization and commoditization of human life emerges from a disconnect between core ethical principles like those outlined above and the oughtness they imply (Matthew 7:21-23; 25:41-46). Too often we fail to connect the dots between our moral beliefs and ethical action (cf. Deuteronomy 10:17-19; Psalm 10:2-3, 8-10).

Engage in Christian activism. On a policy level, Christians and churches should exercise greater global awareness and actions relating to common pathways that lead to the exploitation of human lives: weak, ineffective and loosely enforced immigration laws, sex and human organ tourism, and wars.

Eliminate personal moral wickedness and complacency about our communities. On a local level, complacent faith groups and individual Christ-followers must work actively to eliminate knowing (e.g. pornography, sex tourism; cf. also undocumented laborers) and unwitting personal involvement and economic contribution to such activity (e.g. blind consumerism; viewing TV shows and commercials that dehumanize women and children and financially supporting their corporate advertisers). Christ-love in word and deed is diligent to protect the vulnerable at all levels of need (James 1:27).

Engage in Christian activism. On a policy level, Christians and churches should exercise greater global awareness and actions relating to common pathways that lead to the exploitation of human lives: weak, ineffective and loosely enforced immigration laws, sex and human organ tourism, and wars.

Eliminate personal moral wickedness and complacency about our communities. On a local level, complacent faith groups and individual Christ-followers must work actively to eliminate knowing (e.g. pornography, sex tourism; cf. also undocumented laborers) and unwitting personal involvement and economic contribution to such activity (e.g. blind consumerism; viewing TV shows and commercials that dehumanize women and children and financially supporting their corporate advertisers). Christ-love in word and deed is diligent to protect the vulnerable at all levels of need (James 1:27).

Conclusion

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose legacy was remembered 20 January 2025, once lamented, "There was a time when the church was very powerful—in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society. Small in number, they were big in commitment. They were too God-intoxicated to be 'astronomically intimidated.' . . .

. . .By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests. Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church's silent—and often even vocal sanction of things as they are.

But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today's church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust."

Indeed, millions of people are disgusted with and walking away from the church because its passion to challenge injustice and render aid to the helpless and hopeless has grown cold (Revelation 3:15). Dr. King heard Christ's call in a previous generation to put an end to slavery. I believe that Jesus Christ is calling the church in this generation to rise up and put an end to human trafficking's sexual slavery and domestic servitude.

Prayerfully yours,

Larry C. Ashlock

. . .By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests. Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church's silent—and often even vocal sanction of things as they are.

But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today's church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust."

Indeed, millions of people are disgusted with and walking away from the church because its passion to challenge injustice and render aid to the helpless and hopeless has grown cold (Revelation 3:15). Dr. King heard Christ's call in a previous generation to put an end to slavery. I believe that Jesus Christ is calling the church in this generation to rise up and put an end to human trafficking's sexual slavery and domestic servitude.

Prayerfully yours,

Larry C. Ashlock

Posted in Pathway Perspectives